The challenge of learning with mobiles (LWM) approaches in the Global South

‘If you want to hide something, put it in a book.’ This quip from Alphaxard Kimani, farmer-philosopher of central Kenya, programme leader for The International Small Group and Tree Planting Program (TIST), and long-time friend and colleague, succinctly captures the core problem of learning with mobiles (LWM) strategies in many rural communities across the Global South: most LWM strategies are text-based and most text-based approaches to learning are ineffective.

Kimani’s point is that traditional approaches to learning don’t always resonate with learners. This is the challenge facing LWM approaches in the rural communities where Kimani lives and works: LWM initiatives tend to be derivatives of formal classroom environments and are misaligned with the pedagogical needs of rural adult learners accustomed to educational models based in non-formal small group dialogue.

Kimani is no stranger to the requirements of learners in rural East African communities. He is an expert small group trainer, who for 15 years has been helping adult learners across East Africa use dialogue to facilitate learning within non-formal small groups. Therefore, he knows that typical LWM approaches fail to employ community-based ground rules like kujengana (‘to build up’ in Swahili) and miss an opportunity to root the pedagogy within the lived experience of the small groups.

This is further compounded by the myriad of infrastructure and economic challenges faced in these communities, where there are few smart phones, pay-as-you go data usage models, and limited internet access. Too often the inherent possibilities of mobile technology focus on the capabilities of the technology and do not adequately conform to the affordances available to rural learners, a crucial oversight when working with rural East African residents who face technological access challenges.

Such challenges raise a simple yet difficult question: can a LWM approach address this misalignment?

A learning with mobiles platform designed for rural communities

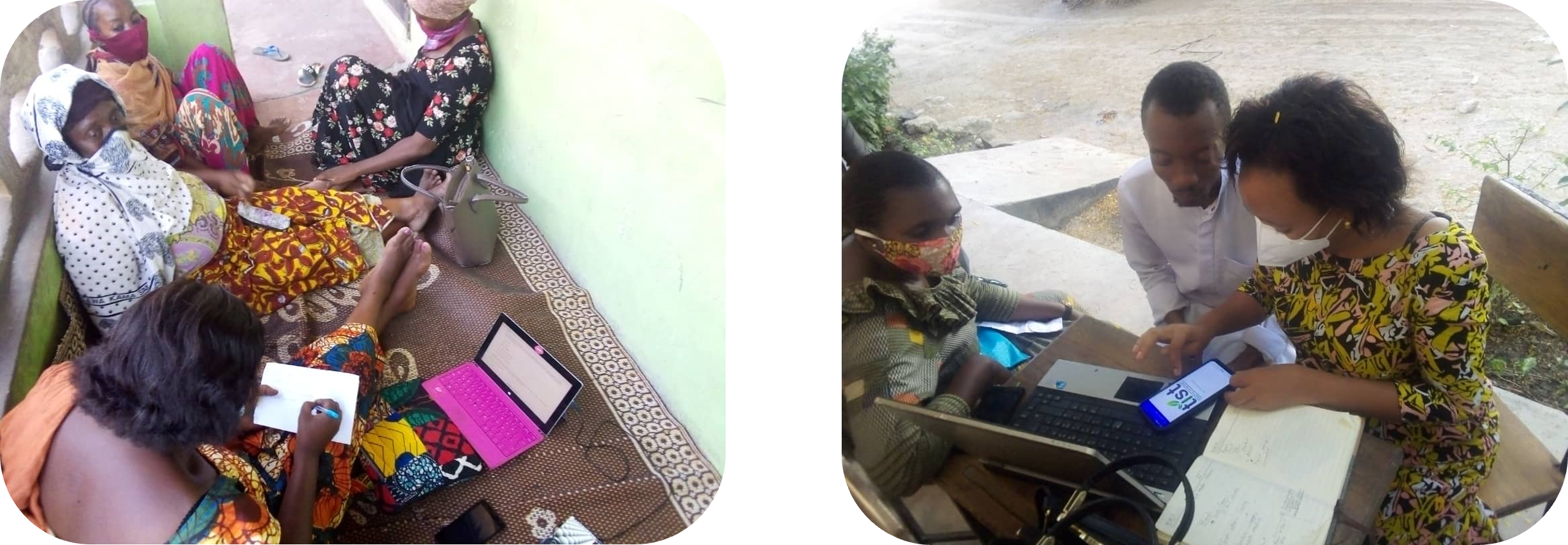

TIST farmers in Eastern Tanzania practicing a practice called ‘Conservation Farming’ after watching demonstration videos and engaging content in the TIST Learning Centre.

Photo Credit – Mary Gemela

An ongoing Design Based Research project, started as my doctoral project and implemented in partnership with TIST, has sought to answer this question. Over the last three years, we’ve attempted to align non-formal dialogic learning with mobile learning pedagogy while considering the technological affordances available to mobile phone users in rural East Africa.

Called the TIST Learning Centre, this free-to-use learning platform serves adult subsistence farmers across Kenya, Uganda, Tanzania, and now southern India. TIST Learning Centre breaks away from past forms of knowledge production and content delivery by reinterpreting how we support and facilitate learning in the rural Global South, with a focus on:

- Offline access

- Low bandwidth functionality

- Economic resource constraints

- Diversity of participant educational background

- Face-to-face small group dialogic pedagogy

The platform is developed around a ‘bring your own device’ (BYOD) approach to scalability and requires no additional hardware to operate. Learning content is available in English and Swahili, with translation into indigenous tribal languages and Tamil coming soon, and it is presented in text and aurally through recordings in local dialects. The current suite of educational content, developed by TIST participants, is primarily focused on agricultural education, the carbon cycle and carbon markets, and TIST programmatic. Learners primarily engage with content to improve farming techniques and to explore the TIST programme. Efforts to expand the range of content are ongoing, with an expressed desire from learners for a greater range of topics such as theology, literature, and science.

Enhancing small group dialogue through mobile learning

The face-to-face interactions take place between peers within a small group, where knowledge is often shared through demonstration, such as a local farmer showing fellow small group members how to create green manure. These demonstrations, traditionally done in situ at a small group member’s local farm, are where participants create content for the platform.

Building from long-standing oral traditions of learning, Kimani and his colleagues at TIST have honed a set of ground rules for supporting dialogue amongst these small groups:

- Rotating leadership at every group meeting

- Focus on facilitation and servanthood rather than monologic domination

- A unique pedagogical construct known as kujengana, which is the act of small group members verbally recognising the positive contributions of the current leader.

The act of rotating leadership allows each member to experience this positive feedback in the form of kujengana on a regular basis, encouraging confidence and fostering a sense of purpose and community.

The TIST Learning Centre supports and enhances this peer-to-peer exchange by allow participating farmers to capture demonstrations via mobile video recording, which is shared via WhatsApp. These videos are then incorporated into the modules within the TIST Learning Centre, expanding their reach and scope. The Learning Centre provides an opportunity for farmers to share knowledge beyond the geography of their respective rural community and has become a valuable tool to capture and disseminate local knowledge.

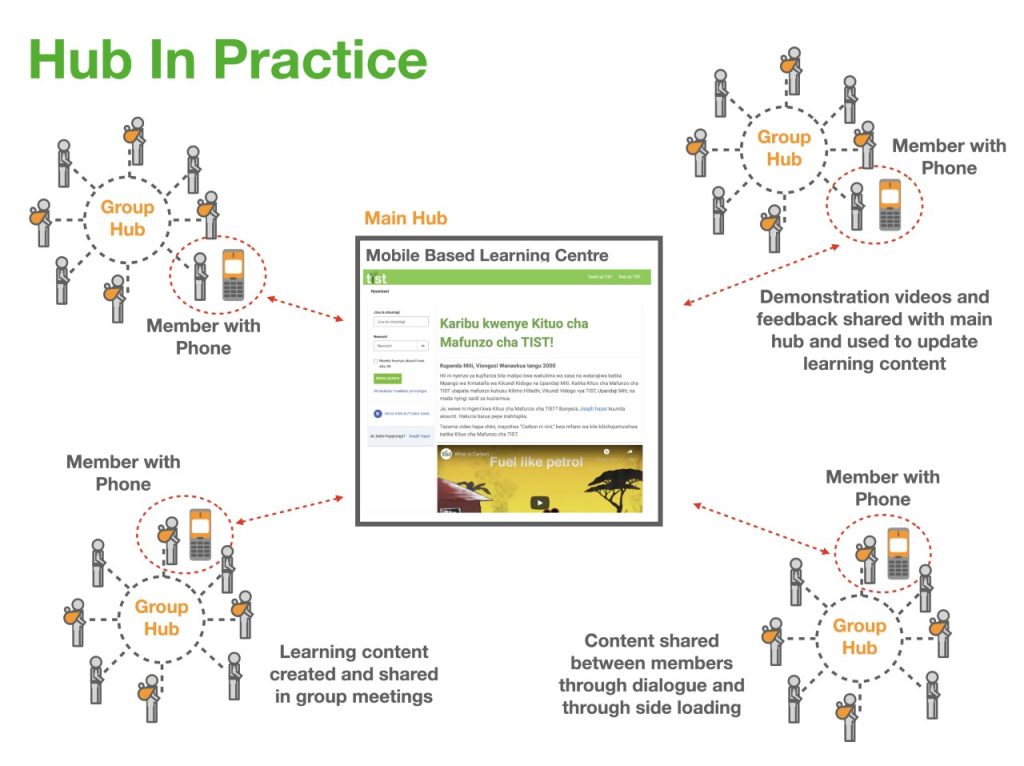

Small groups in Eastern Tanzania using side-loading and the Hub model to share and discuss digital content. Photo credit – Mary Gemela

Using small group dialogue to overcome the digital divide

There are pernicious digital infrastructure challenges throughout the Global South. We have found that 60 percent of TIST Learning Centre users access the content on behalf of a small group, simply because connectivity is too expensive and coverage too sparse for each individual to access content on their own devices. When one person downloads the content, it allows individuals to share costs while minimising the need to travel long distances to obtain connectivity.

For example, Joseph, a TIST member in rural Northeast Uganda, lacks reliable network access in his home community. Therefore, he and his colleagues take turns busing each other’s smartphones to a central town once a week to connect to the network and send and receive email. Such usage habits have profound ramifications for the design of mobile education platforms

In fact, we’ve characterised this new approach to mobile learning as the hub model. In the hub model, a single user accesses learning content on the LWM platform and then shares the content a small group (the hub), either directly through dialogue or via an affordance colloquially called ‘side-loading.’ Side-loading involves downloading content to a mobile device and sharing material with other handsets through either a Bluetooth connection or a micro SD card. The hub model allows digital education to function within the limits of digital access in the Global South.

A new LWM pedagogy supporting learners in rural East Africa

However, the hub model also offers a unique benefit: when the side-loaded content is shared amongst small group members, the material acts as a catalyst for dialogic interactions within the small group. As a pedagogy, it leverages indigenous oral traditions along with simple technological affordances to overcome. This is, to again use the words of Kimani, how we make education ‘sticky’ in rural East Africa.

A TIST farmer and trainer in Kenya explains the importance of this approach…

“Even adopting (the ground rules) for other farmers is huge, because when you go to a farmer and tell them we are farmers like you, they immediately adopt because they say even if a farmer can do this, even me I can do.

So that is how we are reaching out to members and farmers. They are very much excited to see that people are not coming with big cars and big offices, they are being served by their fellow farmers.”

Further research for LWM in the Global South

The LWM platform now has 800 active users and is steadily growing. Analysis of the efficacy of this project has yielded a set of Design Principles for use in LWM approaches in rural communities in the Global South. Ongoing research will test and refine these Design Principles through a deeper assessment of the quality of dialogue produced by this model, investigating the extent to which the model enhances conversations, supports creative problem solving, and achieves long-term learning objectives. Future developments underway include a WhatsApp-based ‘edubot,’ developed in partnership with Meta and InfoBip, which will investigate the ways in which AI can assist in supporting dialogic education in this context.

Findings from this research suggest that adoption of indigenous approaches to dialogic learning can be effective for LWMs in rural East Africa while providing a mechanism to mitigate the digital divide. These findings offer both practical and theoretical insights to researchers and practitioners exploring the use of mobile phones as a tool for learning within rural communities of the Global South, and the concept of kujengana introduces a compelling pedagogical construct for supporting dialogue across all contexts.

Relevance to the Digital Education Futures Initiative

This model is indicative of the types of projects supported by DEFI: digital education should not be about making text-based material more efficient to consume, it should be about leveraging technology to create learning experiences that are immersive, experiential, dialogue-driven and transformative. As DEFI looks to the future we seek to guide the creation of a more inclusive global education system that transcends wealth, class, geography and time. As DEFI grows it will continue to support approaches to digital education which use the affordances of technology to expand interaction and facilitate human flourishing.

Kevin Martin

Centre Manager, DEFI

Kevin Martin is the centre manager at DEFI, responsible for strategic planning, financial management, and day-to-day operations. His professional background lies at the intersection of social innovation and education, and he has spent much of the last 20 years working on related initiatives in East Africa.

0 Comments